Prevotellin-2, an antibiotic found in the human intestine, has shown anti-infective efficacy compared to polymyxin B, an FDA-approved antibiotic used today to treat infections drug resistance, suggesting that the human microbiome may one day contain antibiotics. get a clinical application. Credit: Cesar de la Fuente, Ami S. Bhatt

The average human gut contains about 100 trillion microbes, many of which are constantly competing for scarce resources. César de la Fuente, Associate Professor of the Vice President in Bioengineering and Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering says in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, in Psychiatry and Microbiology in the Perelman School of Medicine, and Chemistry in the School of Engineering and Applied Science. School of Arts and Sciences.

“You have all these bacteria living together, but they’re also fighting each other. That kind of environment can encourage innovation.”

In that conflict, de la Fuente’s lab sees an opportunity to find new antibiotics, which could one day contribute to people’s defense against drug-resistant bacteria. After all, if the bacteria in the human gut have to develop new tools to fight each other to survive, why don’t they use their own weapons?

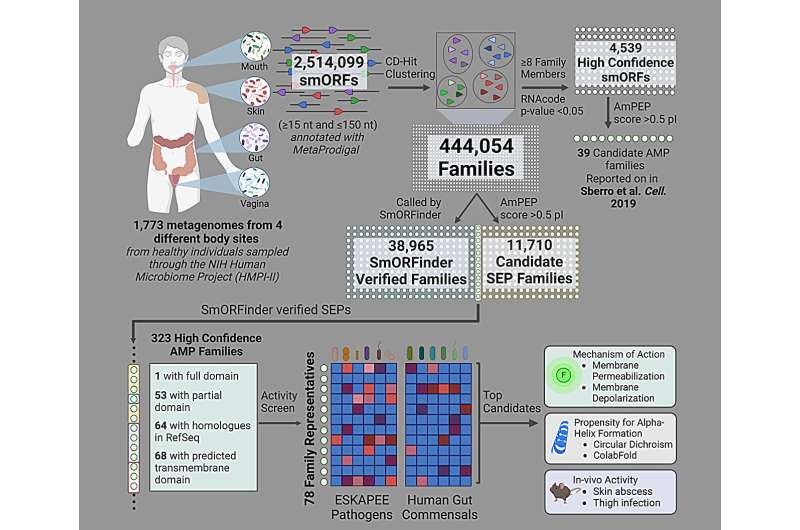

In paper to A cellThe labs of de la Fuente and Ami S. Bhatt, Professor of Medicine (Hematology) and Genetics at Stanford, analyzed the gut microbes of nearly 2,000 people, discovering many new antibiotics that could be present.

De la Fuente says: “We think of biology as a source of information. “Everything is just code. And if we can develop algorithms that can sort that code, we can speed up the discovery of antibiotics.”

In recent years, de la Fuente’s lab has made headlines for finding people with antibodies everywhere, from the genetic information of extinct creatures like Neanderthals and woolly mammoths to in many of the bacteria the lab has tested using artificial intelligence.

De la Fuente says: “One of our main goals is to mine the data of living things on Earth as a source of antibiotics and other beneficial molecules.

“Instead of relying on traditional, painful methods that involve collecting soil or water samples and purifying active compounds, we use the vast biological information obtained from genomes, metagenomes and proteoms. This it enables us to discover new antibiotics at digital speed.”

Because bacteria mutate so quickly, de la Fuente and his co-authors hypothesized that an environment that promotes competition—like the human gut—might be home to a wide variety of microbes. -undiscovered attention. “When there’s a lack of resources, that’s where biology really comes up with new solutions,” says de la Fuente.

Penn Engineering and Stanford researchers used AI to help identify potential antibiotic candidates, by analyzing the genetic sequences in nearly 2,000 different human gut microbiomes. Credit: Cesar de la Fuente, Ami S. Bhatt

The team focused on peptides, short chains of amino acids, which have previously shown promise as new antibiotics.

“We digested more than 400,000 proteins,” de la Fuente says, referring to the process in which the AI reads the genetic code and, once trained on a set of known antibiotics, predict which genes may have antimicrobial properties.

“It is interesting that these molecules have a different structure than what is normally considered as viruses,” says Marcelo DT Torres, research assistant in de la Fuente’s laboratory, and first author of the paper. “The compounds we found form a new group, and their unique properties will help us understand and expand the field of biological sequencing.”

Of course, those predictions must be verified experimentally; after finding a few hundred people with antibiotics, the researchers selected 78 to examine the actual bacteria.

After combining these peptides, the researchers exposed bacterial cultures to each peptide and waited 20 hours to see which peptides were successful in inhibiting bacterial growth. In addition, the team later tested the antibiotic in animal models.

More than half of the tested peptides were active—that is, they inhibited the bacterial growth of either friendly or pathogenic bacteria—and the leading agent, prevotellin-2, demonstrated the ability to prevent infection when a compared to polymyxin B, the FDA-approved antibiotic used today. treat multidrug-resistant infections, suggesting that the human gut microbiome may contain antibiotics that may one day find clinical use.

“Identifying prevotellin-2, which has the same activity as one of our last antibiotics, polymyxin B, really surprised me,” says Bhatt.

“This suggests that mining the human microbiome for new and exciting classes of antimicrobial peptides is a promising avenue for researchers and clinicians, especially for patients.”

Additional information:

Mining of human microbes reveals untapped source of peptide antibiotics, A cell (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.07.027. www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(24)00802-X

Newspaper articles:

A cell

Provided by the University of Pennsylvania

Excerpt: Mining the microbiome: Discovering new antibiotics in the human gut (2024, August 19) Retrieved August 20, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-08-microbiome-uncovering- antibiotics-human-gut.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for any legitimate activity for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for informational purposes only.

#Mining #microbiome #Discovering #antibiotics #human #gut

Leave a Reply